Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Well coronavirus has well and truly messed everything up, I can honestly say I thought, compared to most, I would be well suited to lockdown. Yet, here I am, after only two days, trying to conjure up ways I can escape the house and keep from, attacking the fridge, (See Figure 1 for a picture of someone who’s enjoying lockdown a bit too much). For me, one good thing has come of all this mayhem; the marathon being moved to the 25th of October, giving more time to get back on track and complete 26.2 miles, which will take perseverance and grit. As Woody Allen famously said “80% of success is showing up”.

Larkin and colleagues (2019) defined grit as the passion and perseverance for long-term goals, entailing working tirelessly towards challenges, maintaining their interest and effort over months, regardless of adversity, failures and plateaus in progress. For me, the development of grit is essential for the upcoming months due to an increase in adversity through an injury, the challenge of getting back to running and coming to terms with starting my training program from the start, all the time maintaining my enjoyment throughout.

Scholars have suggested that people who possess the dispositional trait, grit, are increasingly likely to be successful in a range of adverse situations (Winkler, Shulman, Beal and Duckworth, 2014). Previously being associated with success in a range of domains; teacher effectiveness (Duckworth et al, 2009), academic performance at leading universities and sporting performance (Duckworth et al, 2007).

More specifically, Grit has been shown to predict achievement and perseverance over and beyond talent, distinguishing successful from less successful athletes. For instance, Conner and Williams (2015) examined whether soccer players who score low and high on the trait grit, can be distinguished based on perceptual-cognitive expertise and sport specific engagement. Results concluded that the grittier the individual the more time in sport-specific activities including training, competition, play and indirect involvement. Additionally, grittier players performed better in comparison to less gritty players on the assessment of situational probability and decision making. Additionally, Quinn and colleagues (2012) concluded that elite players accumulate considerably more time of sport-specific engagement in comparison to less skilled players. Thus, demonstrating a link between sporting performance and grit.

Conversely, while researchers have recognised the effects of grit in specific programs there is a lack of understanding of how grit effects performance, especially within endurance athletes (Eskreis-Winkler et al, 2014). However, the above studies present numerous methodological limitations reducing their reliability when applying to novice athletes like myself; for example, Conner and Williams (2016) sample was limited to elite youth payers presenting a homogenous groups, therefore limiting our knowledge about the relationship of grit and performance within diverse cohorts with ranging skill differences, such as subelite and novice performers.

Consequently, grit has shown to be key for increasing success in a range of domains, Duckworth and colleagues (2007) outlined three ways in which grit can be developed and maintained in the pursuit of long-term goals, which I will apply to my training over the foreseeable months. Primarily, coming to terms with the idea that frustrations are a necessary part of the process, when facing setbacks its key not to give up as it prevents the achievement of long-term goals. According to Duckworth “It’s by making those mistakes that you get better. Making mistakes and failing are normal- in fact they’re necessary.” Therefore, by analysing how you view your mistakes with the goal of learning from them and accepting them can lead to an increase in grittiness. Another method, is looking for ways to make your goals more meaningful, for me this entails writing down and continuously reminding myself why I wanted to run a marathon in the first place, for the feeling I will get when I cross that finish line knowing I persevered even when I wanted to give up, by doing this I will maintain my motivation and drive for training. Finally, is the belief that you can change and grow throughout training rather than obtaining a fixed mindset, this is linked to the belief that I will be fit enough to run a marathon come October due to continuous training and progression, even though at the minute I haven’t run for 6 weeks allowing myself to remain positive and to not give up on my goals.

I believe I already posses a high sense of grit, shown through my decision to continue training for the Liverpool Rock n Roll marathon despite numerous setbacks, like the current pandemic and an injury putting me out of training for over 6 weeks. Interestingly, research also suggests that grit can be learned, specific conditions can develop grit, allowing it to be transferred from one domain to another more challenging situation (Dweck, 2014). For me, swimming is a good example of how grit can be learnt from a young age. From the age of 13, I swam at regional and county level, training for over 16 hours a week both before and after school, as well as competing at weekends. This taught me the true meaning of grit from a young age and how perseverance within training can lead to the success and achievement of goals within the long-term and in times of hardship you always need to focus on the bigger picture. I have recognised that this has transferred over into my training for the marathon, knowing that hard work in the short-term will massively pay off in the future getting me over that finish line on October.

References

Eskreis-Winkler, L., Duckworth, A. L., Shulman, E. P., & Beal, S. (2014). The grit effect: Predicting retention in the military, the workplace, school and marriage. Frontiers in psychology, 5, 36. Retrieved from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00036/full

Larkin, P., O’Connor, D., & Williams, A. M. (2016). Does grit influence sport-specific engagement and perceptual-cognitive expertise in elite youth soccer?. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28(2), 129-138. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2015.1085922

Duckworth, A. L., Quinn, P. D., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2009). Positive predictors of teacher effectiveness. J. Posit. Psychol. 4, 540–547. doi: 10.1080/17439760903157232.

Larkin, P., O’Connor, D., & Williams, A. M. (2016). Does grit influence sport-specific engagement and perceptual-cognitive expertise in elite youth soccer?. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28(2), 129-138. Retrieved from: http://vuir.vu.edu.au/30841/3/Larkin%20-%202015%20-%20Accepted.pdf

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of personality and social psychology, 92(6), 1087. Retrieved from:https://wi01001304.schoolwires.net/cms/lib7/WI01001304/Centricity/Domain/187/Grit%20JPSP.pdf

So, I’ve decided that for the entirety of this process I will no longer think negatively, (definitely won’t happen). But even if the worst does happen and I can’t run the marathon; I’ve realised it doesn’t mean I’ve failed, it just means it will take me a bit longer than everyone else to complete 26.2 miles.

I went to physio on Friday the 6th of March, and while it wasn’t as helpful as I was hoping, I did take one significant factor away. I need to scrap everything I’ve done up to this point, put my ego aside, and start again, setting myself new achievable goals. Which, I now realise probably should have been one of my first blogs, for many important reasons, but you live and you learn.

I’ve named the first stage of goal setting the rehabilitation phase, defined as a problem-solving process delivered by a multi professional team, including numerous treatments, actions and activities (Bovend’Eerdt, Botell, & Wade, 2009). Per Sheil and colleagues (2008) a goal-planning process should be used to guarantee that every individual involved, particularly the patient, agree on the goals of rehabilitation and the methods used to manage these goals, as well as every individuals role in the process. Additionally, it is well recognised that goal setting instigates behavioural change in individuals (Bovend’Eerdt, Botell, & Wade, 2009). For me, setting appropraite goals has been an apparent weakness throughout this process for example, by over training early on in the process and attempting to go back to training even when my body was evidently not ready. For me this has been a massive learning curve by highlighting the need for recovery and that training is quite literally a marathon not a sprint.

Consequently, certain characteristics of goals need to be met for effective goal setting (Hurn, Kneebone, &, Cropley, 2006), such as:

1) The goal should be relevant to the given individual

2) The goal should be achievable, realistic and relevant, yet challenging

3) The goal should be specific thus allowing the goal to be measured

Yet, while it’s clear that goal setting is key for success within a sporting domain, for instance, Weinburg and colleagues (1993) investigated the effectiveness of goal setting, in a sample of 678 professional college athletes. Results showed that all athletes engaged in goal setting to enhance performance, and reported their goals to be highly effective, as well as improving overall performance and enjoyment throughout training, thus demonstrating the need for efficient goal setting within a sporting environment. Yet, little research has been applied to the most effective method of goal setting after an injury leaving numerous unanswered questions (Smith, Ntoumanis, & Cropley, 2006), such as:

1) What is an appropriate time frame?

2) What Is an appropriate number of goals?

3) How should I specify or write a goal?

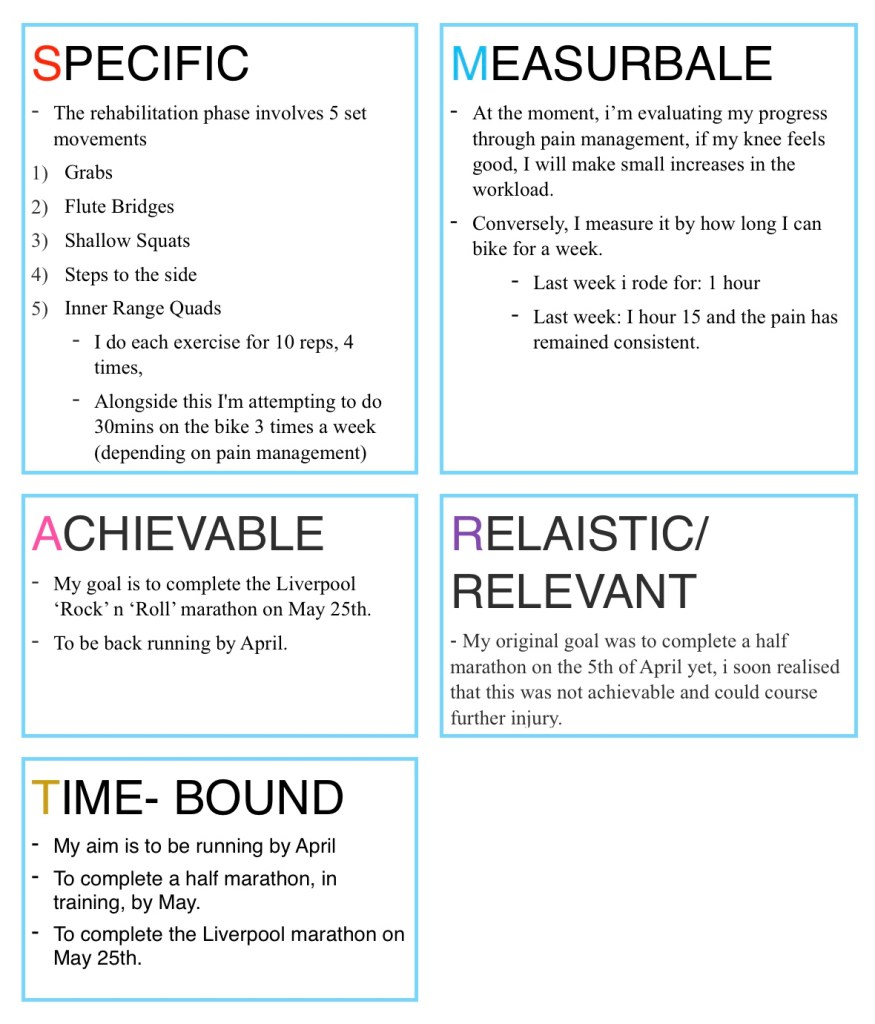

However, it is generally agreed upon that a goal should be specific, measurable, achievable, realistic/relevant, and timed (SMART; Wade, 1999). See Figure 1 for a description:

In order to create effective and appropriate SMART goals I applied each concept to my training, shown below in Figure 2:

By setting SMART goals, most importantly setting realistic goals, has enabled me to rationalise the next three weeks, thereby increasing the likelihood of recovering and being able to run again effectively. Additionally, Wade and Halligan (2004) suggested that its key to acknowledge that goals are hierarchical in nature; the first of which is time: the separation of short-term (being able to run), medium-term (completing a half marathon), and long-term goals (completing a marathon). The second of which is on a conceptual level, such as maintaining psychological and physiological well-being through social participation and activities. Currently, social participation is crucial to maintaining my goals, even though by attending the Born to Run lectures on both a Monday and Tuesday tend to leave me feeling negative about myself through not completing runs or the Anglesey Half marathon, its clear that by failing to attend lectures I would begin to isolate myself from the group leading to a decrease in motivation.

Social isolation is referred to a complete or near-complete absence of contact between a society (Born to Run group) and an individual. Cacioppo (2014) measured the effects of social isolation within college students, showing that a perceived sense of exclusion can cause a heightened sensitivity to social threats, and can cause a decrease in motivation as well as impairing physical and mental wellbeing. This indicating that I need to continue to attend each week in order to maintain focus and motivation in the pursuit of achieving my goals in the long-term, as well as maintaining my enjoyment within the course that I have experienced thus far.

In the next 3 weeks, its imperative that I stick to my goals, without getting ahead of myself, to meet my short, medium and long-terms goals without any further setbacks. The module, up this point, has proven to be one of my biggest challenges, not physically, (ironic considering I can’t do anything because of my knee), but mentally, by picking myself back up repeatedly when I have the urge to give up.

References

Bovend’Eerdt, T. J., Botell, R. E., & Wade, D. T. (2009). Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: a practical guide. Clinical rehabilitation, 23(4), 352-361. Retrieved from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0269215508101741?casa_token=6frHVdMA9_QAAAAA:WNi9B-PGQuERk6tnf7sTiY3BXeir3xrDFzsDyB8h5t7zZL6jRjf1mWLM4pWArO_DAa14uVWICNCpvw

Shiell A, Hawe P, Gold L. Complex interventions or complex systems? Implications for health economic evaluation. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 2008; 336: 1281–83. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2413333/

Locke EA, Latham GP. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. A 35-year odyssey. Am Psychol 2002; 57:705–17. Retrived from: http://farmerhealth.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Building-a-Practically-Useful-Theory-of-Goal-Setting-and-Task-Motivation-A-35-Year-Odyssey.pdf

Hurn, J., Kneebone, I., & Cropley, M. (2006). Goal setting as an outcome measure: a systematic review. Clinical rehabilitation, 20(9), 756-772. Retrieved from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0269215506070793?casa_token=DsJbpY4gI-UAAAAA:DejeMRtUedsKN9dEUd5boaegqf-svMjdXNZahcX_RZigoPGPFCTvTLoExp51xJMKUHLfG4_dEzbjZw

Amiot, C. E., Gaudreau, P., & Blanchard, C. M. (2004). Self-determination, coping, and goal attainment in sport. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 26(3), 396-411. Retrieved from: http://selfdeterminationtheory.org/SDT/documents/2006_AmiotGaudreauBlanchard_JSpEP.pdf

Weinberg, R., Burton, D., Yukelson, D., & Weigand, D. (1993). Goal setting in competitive sport: An exploratory investigation of practices of collegiate athletes. The Sport Psychologist, 7(3), 275-289. Retrieved from: https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/tsp/7/3/article-p275.xml

Smith, A., Ntoumanis, N., & Duda, J. (2007). Goal striving, goal attainment, and well-being: Adapting and testing the self-concordance model in sport. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 29(6), 763-782. Retrieved from: https://research.birmingham.ac.uk/portal/files/10761050/2007_Smith_Ntoumanis_Duda._Goal_Striving_Goal_attainment_well_being.pdf

Wade DT, Halligan PW. Do biomedical models of illness make for good healthcare systems? BMJ 2004; 329: 1398–1401. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC535463/

Cacioppo, J. T., & Cacioppo, S. (2014). Social relationships and health: The toxic effects of perceived social isolation. Social and personality psychology compass, 8(2), 58-72. Retrieved from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/spc3.12087?casa_token=gu7YRU125n0AAAAA:8PM1WfEpEBsgrMdJEnI9rs0-1y1GjlNQFk898u4NGbwg6DzGenZE8nrw3mKBfLkvIHlr9JhwBzr5DKoE

Barry, B. (2002). Social Exclusion, Social Isolation, and. Understanding social exclusion, 13. Retrieved from: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/6516/1/Social_Exclusion,_Social_Isolation_and_the_Distribution_of_Income.pdf

So, I thought this blog would be by far the most positive one so far, (which doesn’t take much), writing it off the back of completing the Anglesey Half Marathon, a big stepping stone to finishing the Liverpool Rock ‘n’ Roll Marathon. Yet, here I am sat in my bed feeling sorry for myself.

Recently, I’ve had a heightened sense of perceived stress towards running and netball, predominately due to the unwavering pain in my ankles and knees which up until Wednesday I thought I could cope with. Brewer (2003) suggested that psychological factors, especially stress, are a key antecedent to injuries and play an essential role in injury rehabilitation. For me, in the past week I had two challenges, the first was the netball cup semi-final on February 26th, (made considerably worse by the fact we were missing one of our best players), and the second was the Anglesey half marathon. According to Brewer (2003), stress is defined as when the demands of a situation exceeds the resources to cope with these demands (see Table 1 for behavioural, physical and psychological stress symptoms).

Evidence advocates that athletes who experience increasing levels of stress, in numerous environments, are at a greater risk of being injured (Williams & Anderson, 1998). On the lead up to Wednesday, I knew my knee was bad; neglecting my training plan to focus on being physically capable to train for and play in the semi-final, (which I can now see was not my wisest choice to date); this is depicted further by the Stress-injury model (Williams & Anderson, 1986; refer to figure 1).

The model stipulates that the majority of psychological variables, that influence injury outcome, are linked with stress and a resulting stress response. When sports participants withstand stressful environments, such as a crucial competition, (the cup semi-final or the half marathon, their personality characteristics, (i.e. hardiness, sense of coherence and competitive trait anxiety), their history of stressors, (i.e. past injury history plus life event stress), and coping resources, (i.e. social support, general coping behaviour, stress management and medication), each factor either works in isolation or interactively to the stress response. The model hypothesises that individuals with a history of many stressors and personality characteristics that tend to exacerbate the stress response paired with few coping resources will, when placed in a stressful situation appraise the situation as more stressful and exhibit greater physiological activation and attentional disruptions, compared to individuals with the opposite psychosocial profile (Williams & Anderson, 1998). The stress-injury model (Williams & Anderson, 1986) has been applied to numerous sporting environments, for instance Kim and Duda (2003) found that football players who experienced high levels of life stress were more likely to become injured than players who experienced little stress in other areas of life; correlating with the stress in my own life inducing injury.

When applying the stress-injury model to my training, some factors are of significance, such as, competitive trait anxiety, past injury history and coping resources. Competitive trait anxiety is referred to as when the demands of competition or training surpass an athletes perceived ability, causing stress levels to increase (Hanton, Evans, & Neil, 2003). On the lead up to the netball match on the Wednesday I was completely aware that my knee was not capable of lasting for an hour (due to a previous injury), yet my competitive nature paired with increasing stress levels, heightened by a lack of available players, meant I repeatedly assured myself that it wasn’t as bad as I thought, (helped by the constant pain killers), and ultimately lead to me playing to my own detriment, causing my knee to give up.

Additionally, this was escalated due to insufficient coping skills. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) divided coping skills into two processes: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. Emotion-focused coping regulates emotional responses to the problem, examples include distancing, selective attention and avoidance (Hagger, Chatzisarantis, Griffin, Thatcher, 2005). On the lead up to the half marathon, I chose to focus solely on playing netball thus avoiding the reality that I had to run 13 miles four days later. Going forward I will concentrate on problem-focused coping strategies, referred to as altering or managing the problem that is causing the distress (Hagger, Chatzisarantis, Griffin, Thatcher, 2005), to set up an effective recovery plan by defining the problem, generating solutions and acting accordingly.

Problem-focused coping strategies have successfully been applied to a sporting environment, Kim and Duda (2003) examined the effectiveness of coping strategies on 404 Korean and 318 U.S athletes based on outcome goals. Results showed that the problem-focused coping strategies were positively associated with achieving long-term goals and significantly reduced the time taken out from training due to injury. Consequently, by applying problem-focused coping strategies, seeing a physio on Friday and taking a time out form training, I will hopefully define the problem and generate solutions and return to training as soon as possible.

I am slowly coming to the realisation that I need to focus on the end goal of getting to the starting line of the Liverpool Rock ‘n’ Roll marathon. I need to be smart, let myself heal and get back to training as soon as my body allows.

References

Albinson, C. B., & Petrie, T. A. (2003). Cognitive appraisals, stress, and coping: Preinjury and postinjury factors influencing psychological adjustment to sport injury. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 12(4), 306-322. Retrieved from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/df95/b1ab3ede3b28af9219eafede5108ff9dc871.pdf

Andersen, M. B., & Williams, J. M. (1988). A model of stress and athletic injury: Prediction and prevention. Journal of sport and exercise psychology, 10(3), 294-306. Retrieved from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4247/3a5952fcfae51fe74f3b28b5a3880d79f194.pdf

Brewer, B. W. (2003). Developmental differences in psychological aspects of sport-injury rehabilitation. Journal of athletic training, 38(2), 152. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC164904/

Broxmeyer, H. E., Williams, D. E., Lu, L., Cooper, S., Anderson, S. L., Beyer, G. S., … & Rubin, B. Y. (1986). The suppressive influences of human tumor necrosis factors on bone marrow hematopoietic progenitor cells from normal donors and patients with leukemia: synergism of tumor necrosis factor and interferon-gamma. The Journal of Immunology, 136(12), 4487-4495. Retrieved from: https://www.jimmunol.org/content/jimmunol/136/12/4487.full.pdf?casa_token=nMYUpMFJNswAAAAA:83KHZy9WIs-H_6w61oqY4JuaDJShJqR7mSH6nDUo-y54QmUNSK6cj1YxL2dFNifbX5tiRUtXYf4-Y5w

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping (pp. 150-153). New York: Springer Publishing Company. Retrieved from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5bef/cc8f5b1f19b3e8411d1f00add4c49e42f87e.pdf

Hagger, M. S., Chatzisarantis, N. L., Griffin, M., & Thatcher, J. (2005). Injury Representations, Coping, Emotions, and Functional Outcomes in Athletes with Sports‐Related Injuries: A Test of Self‐Regulation Theory 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35(11), 2345-2374. Retrieved from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02106.x?casa_token=Eqe_BF2UZTAAAAAA:Rw91PI6k3HxCNgOKHb-B8U805ee_IhZ1ZPNEclR4zG6WRhHDkpdrTuHpoj0o41th0VEFSHOjR_CLXnnF

Hanton, S., Evans, L., & Neil, R. (2003). Hardiness and the competitive trait anxiety response. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 16(2), 167-184. Retrieved from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10615806.2003.10382971

Kim, M. S., & Duda, J. L. (2003). The coping process: Cognitive appraisals of stress, coping strategies, and coping effectiveness. The sport psychologist, 17(4), 406-425. Retrieved from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b2e1/b967c3980a00849557bdc3dfce72174aa4bd.pdf

Williams, J. M., & Andersen, M. B. (1998). Psychosocial antecedents of sport injury: Review and critique of the stress and injury model’. Journal of applied sport psychology, 10(1), 5-25. 10.1080/10413209808406375. Retrieved from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10413209808406375?casa_token=TUBIKJMuJCIAAAAA:FKWpmxCkV5A8jDSJ_yuLsW6BFLjCUPpLIync3LjvMk1E90OBez9W5J0pUkOm0TdpqlhZpJuIaqr-EA

The week commencing the 3rd of February started off as usual, netball fitness at 7:30 on Monday morning, followed by a 5.93k run on the Tuesday, including three successful hill sprints, soon coming to the realisation that hill sprints aren’t the most enjoyable. Then on the Wednesday I travelled to Manchester for our first netball away match of the term (see the picture below) and within the first three minutes, of the first quarter, I went over on my ankle (which is a regular occurrence).

I was sat on the bench for the rest of the match watching on, realising that I had little concern for the match, which isn’t great considering I’m the captain, I felt more concerned about the fact that I wouldn’t be able to run for a few weeks, upon reflection I attributed this to my fear of failure.

Fear of failure is referred to as the motive to avoid failure connected with antiparty shame in evaluative situations; it’s a unidimensional construct which shame being the chief fear of failure (Gustafsson, Sagar, & Stenling, 2017). According to Conroy and Metzier (2004), the fear of failure involves behavioural, cognitive and emotional experiences that can stimulate the pursuit of avoidance goals and strategies, such as mastery-avoidance goals, self-handicapping and low achievement. One qualitative study on fear of failure among elite adolescent athletes showed that fear of failure increased negative cognition and concerns about failure, making them feel worried, stressed, tense and scared, and decreased their motivation and self-perception; to adverse effects such as lowered performance (illustrated in the diagram below) and heightened anxiety (Sagar et al, 2009).

Personally, it took me a while to understand why I attached numerous negative emotions with training or competing in sport (see the table below for a full list), especially increased anxiety, a lack of motivation and increased stressed. Yet as I got older I began to comprehend that it stemmed from a young age when I swam competitively. Training 16 hours a week and competing most weekends; I always feared performing badly mainly because of the amount of time, money and effort my parents were putting in, causing me to attribute my fear of failure to several aspects of my life as I got older.

Consequently, spraining my ankle caused me to engage in mastery-avoidance goals, particularly self-handicapping, through-out the third week of my training plan. Experiencing a lack of motivation, positive thoughts, energy and drive. Self- handicapping is explained as proactively reducing effort and producing performance excuses to protect one’s self from negative feedback (Berglas and Jones, 1978). One study by Prapavessis and colleagues (2003) noted that self-handicapping within sport was directly associated with poorer practice and nutrition, for me this couldn’t be more visible, as my nutrition completely went out the window through skipping meals, earring unhealthy (see photos below for some evidence) or snacking consistently, pairing this with my ankle gave me the perfect excuse to go off track. Also, fear of failure can lead to emotion-orientated coping strategies, such as passivity and disengagement (Kuczka & Treasure, 2005); disengagement is explained as the process or action of withdrawing from involvement in a situation, group or activity (Boardely & Kavussanu, 2007). For me, this has been evident in many challenges that I’ve faced, whether that be in form of procrastination when I do university work, retreating from social groups that I don’t feel comfortable in or most importantly neglecting training when I face the slightest adversity.

However, inadequate research has been conducted examining self-handicapping in sport, particularly within elite level performers as well as some studies suggesting that self-handicapping is rare in aa sport settings (Rhodewalt, 1994; Hausenbles & Carron, 1996). Moreover, one study by Gustafsson and colleagues (2011) on elite sprinters suggested that fear of failure did not have a statistically significant effect physical/emotional exhaustion and sport devaluation which is said to predict self-handicapping within a sporting environment; yet this does not override the sum of evidence indicating that self-handicapping is a maladaptive coping strategy causing motivational difficulties that is likely to have a negative effect on long-term performance and development (Prapavesis et al, 2003).

At the beginning of the following training week I set a goal to challenge and correct these maladaptive beliefs through challenging my own self-talk, commonly referred to as an inner voice that provides a consistent monologue, combining conscious thoughts with unconscious beliefs and biases (Tod, Hardy, & Oliver, 2011). Conroy & Metzler (2004) stress that we change behaviour simply by choosing what we say to ourselves, this was a simple and effective change, I began to simply say “I can do it” every time a negative thought occurred and I reminded myself why I wanted to face this challenge in the first place; it wasn’t to become the next Mo Farah but to enjoy and challenge myself.

References

Boardley, I. D., & Kavussanu, M. (2007). Development and validation of the moral disengagement in sport scale. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 29(5), 608-628. Retrieved from: https://core.ac.uk/reader/1631160

Conroy, D. E., & Metzler, J. N. (2004). Patterns of self-talk associated with different forms of competitive anxiety. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 26(1), 69-89. Retrieved from: https://whel-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/openurl?sid=google&auinit=DE&aulast=Conroy&atitle=Patterns%20of%20self-talk%20associated%20with%20different%20forms%20of%20competitive%20anxiety&id=doi:10.1123%2Fjsep.26.1.69&title=Journal%20of%20sport%20%26%20exercise%20psychology&volume=26&issue=1&date=2004&spage=69&issn=0895-2779&vid=44WHELF_BANG_VU4&institution=44WHELF_BANG&url_ctx_val=&url_ctx_fmt=null&isSerivcesPage=true

Tod, D., Hardy, J., & Oliver, E. (2011). Effects of self-talk: A systematic review. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 33(5), 666-687. Retrieved from: https://whel-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/openurl?sid=google&auinit=D&aulast=Tod&atitle=Effects%20of%20self-talk:%20A%20systematic%20review&id=doi:10.1123%2Fjsep.33.5.666&title=Journal%20of%20sport%20%26%20exercise%20psychology&volume=33&issue=5&date=2011&spage=666&issn=0895-2779&vid=44WHELF_BANG_VU4&institution=44WHELF_BANG&url_ctx_val=&url_ctx_fmt=null&isSerivcesPage=true

Hatzigeorgiadis, A., & Biddle, S. J. (2008). Negative Self-Talk During Sport Performance: Relationships with Pre-Competition Anxiety and Goal-Performance Discrepancies. Journal of Sport Behavior, 31(3). Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Stuart_Biddle/publication/291771604_Negative_self-talk_during_sport_performance_Relationships_with_pre-competition_anxiety_and_goal-performance_discrepancies/links/56cc032a08ae96cdd06feeec/Negative-self-talk-during-sport-performance-Relationships-with-pre-competition-anxiety-and-goal-performance-discrepancies.pdf

Kuczka, K. K., & Treasure, D. C. (2005). Self-handicapping in competitive sport: Influence of the motivational climate, self-efficacy, and perceived importance. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 6(5), 539-550. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1469029204000573

Gustafsson, H., Sagar, S. S., & Stenling, A. (2017). Fear of failure, psychological stress, and burnout among adolescent athletes competing in high level sport. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 27(12), 2091-2102. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/sms.12797?casa_token=ExF8FYdsYX0AAAAA:WNMm6trlC1qgNQBQdGhJ6QiY9wJ7kjRxb5Vz_Vq89Fdu5WlKUm7nMYdsev_KBoGolbT6m8z1NcVZmeCA

Conroy, D. E., & Elliot, A. J. (2004). Fear of failure and achievement goals in sport: Addressing the issue of the chicken and the egg. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 17(3), 271-285. Retrieved from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1061580042000191642?casa_token=jjgQcGNhYmIAAAAA:LIf_AOGaYAp7NgRGg8aNkL7j_ksnjJO_BIf84McbEKk6LAVJZ3cyBvSX9f2t30_oRIUJiI1EPtucQg

Hatzigeorgiadis, A., & Biddle, S. J. (2008). Negative Self-Talk During Sport Performance: Relationships with Pre-Competition Anxiety and Goal-Performance Discrepancies. Journal of Sport Behavior, 31(3). Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Stuart_Biddle/publication/291771604_Negative_self-talk_during_sport_performance_Relationships_with_pre-competition_anxiety_and_goal-performance_discrepancies/links/56cc032a08ae96cdd06feeec/Negative-self-talk-during-sport-performance-Relationships-with-pre-competition-anxiety-and-goal-performance-discrepancies.pdf

Jones, E. E., & Berglas, S. (1978). Control of attributions about the self through self-handicapping strategies: The appeal of alcohol and the role of underachievement. Personality and social psychology bulletin, 4(2), 200-206. Retrieved from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/014616727800400205?casa_token=2mjFZO7qyLwAAAAA:bmoK8QVLy8K6Elm9YfqJst2cFIlZXpJQ_O9VdjUrprE6GjuQN_AZiXxt5tuKJ3WfDT7ryJK9Y16oPA

Martin, L. J., Burke, S. M., Shapiro, S., Carron, A. V., Irwin, J. D., Petrella, R., … & Shoemaker, K. (2009). The use of group dynamics strategies to enhance cohesion in a lifestyle intervention program for obese children. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 277. Retrieved from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1471-2458-9-277

Boardley, I. D., & Kavussanu, M. (2007). Development and validation of the moral disengagement in sport scale. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 29(5), 608-628. Retrieved from: https://core.ac.uk/reader/1631160

Tod, D., Hardy, J., & Oliver, E. (2011). Effects of self-talk: A systematic review. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 33(5), 666-687. Retrieved from google scholar: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Tod%2C+Hardy%2C+%26+Oliver%2C+2011&btnG=

Sagar, S. S., Busch, B. K., & Jowett, S. (2010). Success and failure, fear of failure, and coping responses of adolescent academy football players. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 22(2), 213-230. Retrieved from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10413201003664962?casa_token=zXbHaDmEkgMAAAAA:2laZ0suufkeA4DuJHMBA5X7GZo83Y4jy3sNXr8QEz3vHc_quGxEXgi5_kyioyC0H20rS8tqFH4rISw

It was told from a young age that if an individual has unwavering passion they will find a way to accomplish any challenge they face, yet I had never challenged this concept. This all changed when I undertook the challenge of training for a marathon. Consequently, the road to the Liverpool RocknRoll marathon commenced on the 20th of January.

Immediately I was faced with my first hurdle, forming an appropriate training plan through effective goal setting. Goal setting is referred to as a mental training technique that enhances an individual’s commitment regarding the achievement of a personal goal. Both short and long term goals can incite a person to work, overcome setbacks and focus on the task (Lunenbrug, 2011). The first week of my training plain is shown below including my typical week of netball training:

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday |

| 50-minute run 1 hour netball fitness (7:30-8:30) | 45-minute run Netball training 6-8 | 45-minute run 1 hour netball Match | Day off | 7 Miles Netball training 7-9 | 30-minute run | Day off |

Initially, I believed I was more than capable of forming a training plan without accounting for netball training. The depth of my mistake was soon realised whilst completing my long run on the Friday. Originally, my aim was to complete 7 miles (11.26 Km) on Friday yet I only managed to complete 9.07 Km. I wondered if this was due to a lack of resilience.

According, to Subhan (2012) resilience is the capability to bounce back from adverse experiences efficiently and quickly, individuals who possess high levels of resilience show better performance than those who lack the characteristic (Galli, 2005). Due to the notion that individuals who participate in sport constantly face obstacles, setbacks and failures throughout training resilience allows an athlete to adapt their behaviour, ensue positive progression and achieve the equilibrium level (Masten, 2001). Therefore, as training progresses I hope to become increasingly resilient there-by completing my training plan to the best of my ability.

In terms of my training I set unrealistic performance goals. According, to Elliot and McGregor (2001) there are four types of performance goals; performance-approach, performance-avoidance, mastery-avoidance goals and mastery-approach. I believe that I approached training through performance-avoidance goals, commonly referred to as the motivation to avoid displaying normative incompetence. I wanted to avoid doing worse than others which has been shown to significantly decrease performance (Conroy & Elliot, 2005).

For instance, Elliot and colleagues (2006) experimentally induced performance approach and performance avoidance goals prior to a dribbling task. Findings indicated that players who had been instructed to do better than other (performance approach) performed better overall in comparison to players who had been instructed to avoid dong worse than others (performance avoidance). This has made me rapidly readjust the way I approached my training, learning to train more efficiently and gain further knowledge on appropriate training techniques.

References

Giorgi, B., & Boudreau, A. L. (2010). The experience of self-discovery and mental change in female novice athletes in connection to marathon running. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 41(2), 234-267. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alison_Boudreau/publication/233646245_The_Experience_of_Self-

Kingston, K. M., & Hardy, L. (1997). Effects of different types of goals on processes that support. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kingston_Kieran/publication/285762010_Effects_of_Different_Types_of_Goals_on_Processes_That_Support_Performance/links/58c6dd6c92851c653192b21e/Effects-of-Different-Types-of-Goals-on-Processes-That-Support-Performance.pdf

Lunenburg, F. C. (2011). Goal-setting theory of motivation. International journal of management, business, and administration, 15(1), 1-6. Retrieved from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b0b8f55365f02045e1ecaa5/t/5b14d215758d46f9851858d1/1528091160453/Lunenburg%2C+Fred+C.+Goal-Setting+Theoryof+Motivation+IJMBA+V15+N1+2011.pdf

Stoeber, J., Uphill, M. A., & Hotham, S. (2009). Predicting race performance in triathlon: The role of perfectionism, achievement goals, and personal goal setting. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 31(2), 211-245. Retrieved from: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/18975/1/Stoeber_%26_Uphill_Triathlon_2009.pdf

Subhan, S., & Ijaz, T. (2012). Resilience scale for athletes. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 6(2), 171. Retrieved from: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1352857602?pq-origsite=gscholar

Galli, S. J., Kalesnikoff, J., Grimbaldeston, M. A., Piliponsky, A. M., Williams, C. M., & Tsai, M. (2005). Mast cells as “tunable” effector and immunoregulatory cells: recent advances. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 23, 749-786. Retrieved from: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141025?casa_token=A6wL6G_6s14AAAAA%3AxAmLcBo5wMRo4itLwIf-bdEE6mb0NVxI1a03g4dGEVT6CMHWmPdhowTGz9Xsv_OwPcRWX1lgz7FyMg

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American psychologist, 56(3), 227. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X

Elliot, A. J., & McGregor, H. A. (2001). A 2× 2 achievement goal framework. Journal of personality and social psychology, 80(3), 501. Retrieved from: https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2001-16719-011.html

Elliot, A. J., & Conroy, D. E. (2005). Beyond the dichotomous model of achievement goals in sport and exercise psychology. Sport and Exercise Psychology Review, 1(1), 17-25. Retrieved from: http://t012.camel.ntupes.edu.tw/ezcatfiles/t012/img/img/171/Elliot&Conroy2005_17-25_1(1)_SEPR.pdf

This is an example post, originally published as part of Blogging University. Enroll in one of our ten programs, and start your blog right.

You’re going to publish a post today. Don’t worry about how your blog looks. Don’t worry if you haven’t given it a name yet, or you’re feeling overwhelmed. Just click the “New Post” button, and tell us why you’re here.

Why do this?

The post can be short or long, a personal intro to your life or a bloggy mission statement, a manifesto for the future or a simple outline of your the types of things you hope to publish.

To help you get started, here are a few questions:

You’re not locked into any of this; one of the wonderful things about blogs is how they constantly evolve as we learn, grow, and interact with one another — but it’s good to know where and why you started, and articulating your goals may just give you a few other post ideas.

Can’t think how to get started? Just write the first thing that pops into your head. Anne Lamott, author of a book on writing we love, says that you need to give yourself permission to write a “crappy first draft”. Anne makes a great point — just start writing, and worry about editing it later.

When you’re ready to publish, give your post three to five tags that describe your blog’s focus — writing, photography, fiction, parenting, food, cars, movies, sports, whatever. These tags will help others who care about your topics find you in the Reader. Make sure one of the tags is “zerotohero,” so other new bloggers can find you, too.